Fertility and field of study by gender

While women’s participation in higher education has caught up with and surpassed that of men, large gender differences persist in the choice of field of study. To date, we know little about the mechanisms that explain the link between fertility and study disciplines for both men and women. Trimarchi and Van Bavel (2018) aimed to study gender differences in the effect on fertility of earnings potential and gender composition in study disciplines.

Recently, theoretical approaches in family demography have emphasized the role of gender egalitarianism as an engine of fertility both in society at large and within households, highlighting the fact that highly educated women have higher second and third birth rates compared to lower educated women, at least in some contexts (Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015; Goldscheider, Bernhardt, and Lappegård 2015). One reason for such a change may be that the earnings potential of highly educated women has become more important in their fertility decisions so that they show a positive income effect, while at the same time, as men engage more in raising children, the opportunity costs, of parenthood, i.e. the earnings they may renounce to be actively involved in childrearing activities, become a more important factor.

Earnings potential and effect on fertility

In order to address the economic aspect of education and its effects on fertility, in this study the authors have focused on the earning potential entailed by an educational degree. Educational field is a distinctive trait of an individual’s educational path, especially since the expansion of higher education. Since people decide on their field of study relatively early in their life course, it can be assumed to be less affected by fertility (i.e. endogenous with respect to fertility) than income earned around the time of childbearing, since childbearing and childbearing intentions are known to affect income. Endogeneity issues* are especially problematic when detailed information on employment status, occupation, and income are not available, and this is why the authors preferred to look at the earnings potential embodied in the educational degree obtained earlier in the life course rather than at actual current income.

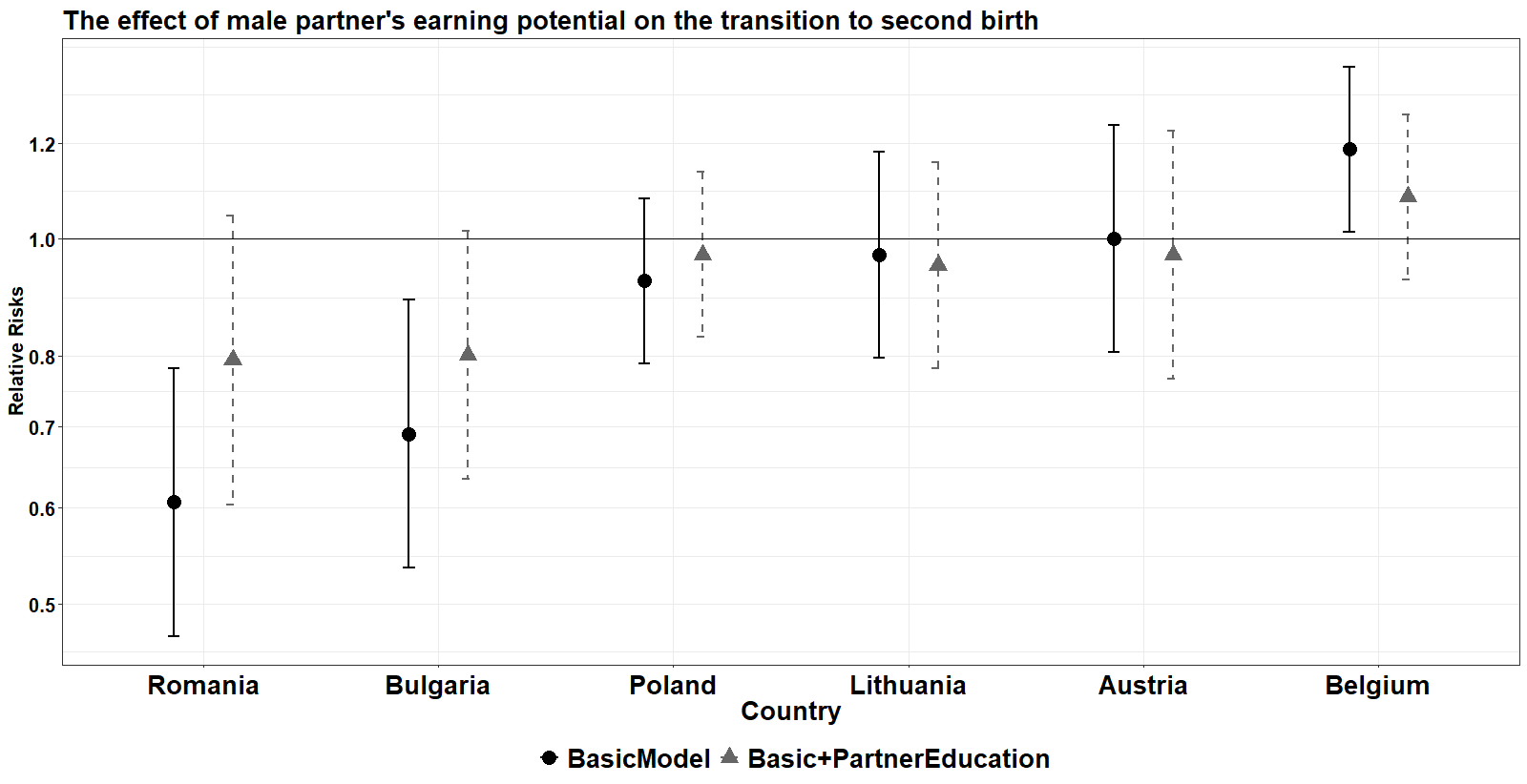

By means of European Labor Force Survey (EU-LFS) data and OLS models the authors estimated earnings potential by country, sex and educational degree. Next, they linked these estimates to the Generations and Gender Surveys (GGS) of Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania. Then, they estimated models for men and women separately by country, accounting for unobserved heterogeneity across birth episodes to analyze the transition to first and second births jointly. This methodology allows to test whether study discipline affects fertility via two mechanisms: earnings potential and gender composition of the study field.

*Two variables are endogenous when they are jointly determined.

Relatively similar fertility behaviors among men and women

The authors did not find any effect of earnings potential regarding the transition to fatherhood, except in Poland, where it has a statistically significant negative effect, meaning that a higher earning potential is associated with lower men’s first birth rates. Still, this effect is not statistically significant anymore when partners’ education is included in the model. Fig. 1 shows the effect of earning potential on men’s second birth rates. The authors found that earnings potential is positively associated with men’s second-birth rates (and to a lesser extent with women’s) in Belgium, whereas it is negatively associated in other countries, with the strongest negative effects in Bulgaria and Romania. Moreover, in the considered contexts the gender composition of the study discipline is more relevant to understanding the transition to first birth rather than second birth.

Note: All models include duration splines, age at first birth, cohorts, father’s and mother’s education, number of siblings.

In sum, the results show great heterogeneity across contexts, but the mechanisms tend to be similar for both men and women within contexts. This study broadens our understanding of the effect of the field of study on the fertility of both men and women by considering two characteristics of the study discipline: earnings potential and gender composition. The study suggests that the drivers of men’s and women’s family behaviour may be more similar than is often expected. Societal changes that have occurred in the last three decades may lead to a stronger role for men in fertility decision-making, which may remain unnoticed if we continue to focus only on women.

References:

- Esping-Andersen, G. et Billari, F.C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review 41(1) : 1–31.

- Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., et Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review 41(2) : 1 207-239.

Source: Alessandra Trimarchi, Jan Van Bavel, 2018, Gender differences and similarities in the educational gradient in fertility: The role of earnings potential and gender composition in study disciplines, Demographic Research, vol. 39, p. 381–414.

Contact: Alessandra Trimarchi

Online: September 2019